Modern system of classification

A pattern of groups nested within groups was specified by Linnaeus' classifications of plants and animals, and these patterns began to be represented as dendrograms of the animal and plant kingdoms toward the end of the 18th century, well before On the Origin of Species was published. The pattern of the "Natural System" did not entail a generating process, such as evolution, but may have implied it, inspiring early transmutationist thinkers . Among early works exploring the idea of a transmutation of species were Erasmus Darwin's 1796 Zoönomia and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck's Philosophie Zoologique of 1809. The idea was popularized in the Anglophone world by the speculative but widely read Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, published anonymously by Robert Chambers in 1844.

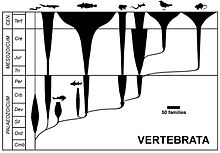

With Darwin's theory, a general acceptance quickly appeared that a classification should reflect the Darwinian principle of common descent. Tree of life representations became popular in scientific works, with known fossil groups incorporated. One of the first modern groups tied to fossil ancestors was birds. Using the then newly discovered fossils of Archaeopteryx and Hesperornis, Thomas Henry Huxley pronounced that they had evolved from dinosaurs, a group formally named by Richard Owen in 1842. The resulting description, that of dinosaurs "giving rise to" or being "the ancestors of" birds, is the essential hallmark of evolutionary taxonomic thinking. As more and more fossil groups were found and recognized in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, palaeontologists worked to understand the history of animals through the ages by linking together known groups. With the modern evolutionary synthesis of the early 1940s, an essentially modern understanding of the evolution of the major groups was in place. As evolutionary taxonomy is based on Linnaean taxonomic ranks, the two terms are largely interchangeable in modern use.

The cladistic method has emerged since the 1960s. In 1958, Julian Huxley used the term clade. Later, in 1960, Cain and Harrison introduced the term cladistic. The salient feature is arranging taxa in a hierarchical evolutionary tree, with the desideratum that all named taxa are monophyletic. A taxon is called monophyletic, if it includes all the descendants of an ancestral form. Groups that have descendant groups removed from them are termed paraphyletic, while groups representing more than one branch from the tree of life are called polyphyletic. Monophyletic groups are recognized and diagnosed on the basis of synapomorphies, shared derived character states.

Cladistic classifications are compatible with traditional Linnean taxonomy and the Codes of Zoological and Botanical Nomenclature. An alternative system of nomenclature, the International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature or PhyloCode has been proposed, whose intent is to regulate the formal naming of clades. Linnaean ranks will be optional under the PhyloCode, which is intended to coexist with the current, rank-based codes. It remains to be seen whether the systematic community will adopt the PhyloCode or reject it in favor of the current systems of nomenclature that have been employed (and modified as needed) for over 250 years.

Kingdoms and domainsedit

Well before Linnaeus, plants and animals were considered separate Kingdoms. Linnaeus used this as the top rank, dividing the physical world into the plant, animal and mineral kingdoms. As advances in microscopy made classification of microorganisms possible, the number of kingdoms increased, five- and six-kingdom systems being the most common.

Domains are a relatively new grouping. First proposed in 1977, Carl Woese's three-domain system was not generally accepted until later. One main characteristic of the three-domain method is the separation of Archaea and Bacteria, previously grouped into the single kingdom Bacteria (a kingdom also sometimes called Monera), with the Eukaryota for all organisms whose cells contain a nucleus. A small number of scientists include a sixth kingdom, Archaea, but do not accept the domain method.

Thomas Cavalier-Smith, who has published extensively on the classification of protists, has recently proposed that the Neomura, the clade that groups together the Archaea and Eucarya, would have evolved from Bacteria, more precisely from Actinobacteria. His 2004 classification treated the archaeobacteria as part of a subkingdom of the kingdom Bacteria, i.e., he rejected the three-domain system entirely. Stefan Luketa in 2012 proposed a five "dominion" system, adding Prionobiota (acellular and without nucleic acid) and Virusobiota (acellular but with nucleic acid) to the traditional three domains.

| Linnaeus 1735 |

Haeckel 1866 |

Chatton 1925 |

Copeland 1938 |

Whittaker 1969 |

Woese et al. 1990 |

Cavalier-Smith 1998 |

Cavalier-Smith 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 kingdoms | 3 kingdoms | 2 empires | 4 kingdoms | 5 kingdoms | 3 domains | 2 empires, 6 kingdoms | 2 empires, 7 kingdoms |

| (not treated) | Protista | Prokaryota | Monera | Monera | Bacteria | Bacteria | Bacteria |

| Archaea | Archaea | ||||||

| Eukaryota | Protoctista | Protista | Eucarya | Protozoa | Protozoa | ||

| Chromista | Chromista | ||||||

| Vegetabilia | Plantae | Plantae | Plantae | Plantae | Plantae | ||

| Fungi | Fungi | Fungi | |||||

| Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia |

Recent comprehensive classificationsedit

Partial classifications exist for many individual groups of organisms and are revised and replaced as new information becomes available; however, comprehensive, published treatments of most or all life are rarer; recent examples are that of Adl et al., 2012 and 2019, which covers eukaryotes only with an emphasis on protists, and Ruggiero et al., 2015, covering both eukaryotes and prokaryotes to the rank of Order, although both exclude fossil representatives. A separate compilation (Ruggiero, 2014) covers extant taxa to the rank of family. Other, database-driven treatments include the Encyclopedia of Life, the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, the NCBI taxonomy database, the Interim Register of Marine and Nonmarine Genera, the Open Tree of Life, and the Catalogue of Life. The Paleobiology Database is a resource for fossils.

Comments

Post a Comment